With apologies for a long preface, I’ll share the bottom line up front: Access for students motivated to pursue higher education has been a topic for years. However, due to anti-DEI actions, pushed by the GOP in Texas and elsewhere, access may become more challenging and, unless we’re careful, the student resources needed to ensure successful outcomes may disappear.

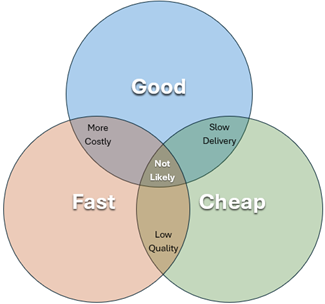

As for preliminaries, I’ve shared this Venn diagram many times over the years. In an online design community conversation, I saw the good, fast, cheap diagram that I’ve recreated below:

In the conversation I was involved with, we were talking about the outcomes associated with working with a client on a particular design project. As a design development and production model, this concept map reflects the amount of work, energy and creativity required to satisfy a client within reasonable cost and time constraints. The essential idea is simple: you can have two of the three options, but not all three. Picking any two would automatically eliminate the third. In other words, good and fast would not be cheap; fast and cheap would not be good; and cheap and good would not be fast.

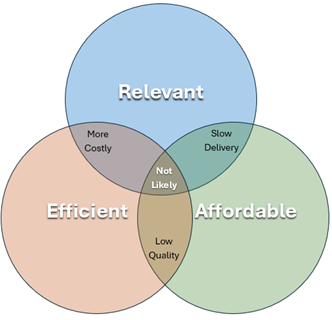

It occurred to me the other day that a similar tension exists between the ideas of relevance, affordability, and efficiency in higher education. I’ve fleshed out the idea below in a similar Venn diagram:

With some changes to the nomenclature that are now consistent with the intent of a higher education model, the same problem faces faculty when they embark on the design and delivery of a curriculum: picking two would automatically eliminate the third. In other words, relevant and efficient would not be cheap; efficient and affordable might suffer from quality issues; and affordable and relevant would not likely be very fast. And, like the design version, this concept map reflects the amount of work, energy and creativity required to have students meet the outcomes needed to align with their professional goals within reasonable cost and time constraints.

Schools that meet outcomes are thought of as being of high quality, as program relevance prepares the student to enter and successfully compete with others in a professional setting. But the efficiency of a program is also important, not just for the sake of allowing students to complete quickly so that they can meet their professional aspirations, but also for the sake of ensuring that the curriculum is minimally redundant. This balance of relevance and efficiency is indeed more costly but, in the long term, it’s the most viable option to ensure good results.

While costs have recently plateaued, the cost for higher education has outstripped inflation for the last two decades. And cost is still the primary hurdle for most students. Affordability in the Venn diagram is the one that gets the most attention, but it’s more complicated. In fact, as costs are often the only factor that drives decisions, there is an increasing risk for creating a negative feedback loop, especially when economic circumstances alone drive school choice decisions. In short, when those schools that are affordable are often the only choice, they may not be a good choice. This is true especially if the schools lack the resources that more wealthy systems have, and then the chance of at-risk student attrition increases dramatically.

Again, it is a multi-faceted issue and requires attention to each facet to make progress. After the financial issues, the most obvious hurdles are organized around a general category called preparedness, and yet others are clustered around students’ personal issues that can both directly and indirectly create barriers. All these issues – financial, academic, and personal – don’t end when the prospective student is admitted. They continue to be attrition categories after enrollment. Student support for these at-risk areas provides a set of vital lifelines for students who are managing complicated lives in addition to their efforts in the classroom. The clear connection between support and the success of students has been demonstrated at multiple levels in a variety of settings and school types, including both private and public institutions. Intentional interventions around these three risk categories work, and the numbers are there to prove it.

So, we have clearly defined the issues and we know how to address them, but there is one other element that is foundational to all these risk categories. Certain racial groups, including Black, Hispanic, and Native American students, face other barriers to higher education. Some of these barriers are cultural and are often thought of as internal (unique to the student), and others are structural and generally considered external (systemic in nature). Not surprisingly, these ideas are opposite sides in a long-simmering argument about racial outcomes in higher education. As usual, things get polarized, and so most of what are in the current political conversations are missing substantive non-partisan attention to both. But to ignore them is not an option as these challenges and the positions people take around them have history that could merit consideration for both how we structure any continued support and who is entitled to receive it.

As noted by Linda Darling-Hammond in her Brookings Institution article, Unequal Opportunity: Race and Education, one side posits that outcome gaps for non-white students are about the internal factors; i.e., lack of will (laziness), indifference to aspirational economic goals, or at the very worst, racist and supremacist assertions that deficiencies in genetics are manifesting themselves in a lack of ability. On the other side, external factors reflect the generations of non-white students as being “educated in wholly segregated schools funded at rates many times lower than those serving whites and [which] were excluded from many higher education institutions entirely,” Darling- Hammond’s assertion is that this has created significant structural deprivations that feed future expectations.

What’s interesting to me is that both groups cling to the same data points that reflect substantive yet irregular improvements by non-whites in standardized testing and the closing of the so-called achievement gap. This gap, particularly with Black students, has varied over the years since the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling in 1954, but as Jill Barshay notes in her article PROOF POINTS: Tracing Black-white achievement gaps since the Brown decision, Black achievement is intertwined with poverty, concluding that “so many Black students are concentrated in high-poverty schools, where teacher turnover is high, and students are less likely to be taught by excellent, veteran teachers. Meanwhile administrators are struggling with non-academic challenges, such as high rates of homelessness, foster care, violence and absenteeism that interfere with learning. None of these are problems that schools alone can fix.”

While there are no answers here, my worry (and the challenge) is that we keep an eye on the elimination of DEI on college campuses to ensure that they don’t eventually cascade into a withdrawal of support for the very programs that have been working to close the gaps in tests and real student outcomes.

Under the guise of eliminating DEI, funding for programs that address the needs of risk categories (financial, preparedness, and personal) are at risk of being eliminated, not because they are ineffective, but because of who they serve.